Group C Racing 1982 - 1993

The Rise and Fall

Group C was the Sports Prototype class introduced in 1982 along with Group A and Group B for production cars. The series ran in varying forms from 1982 until 1993, when a change of engine regulations killed it as a viable form of racing.

Until the introduction of the 3.5 litre class, Group C was a 'fuel consumption' series. Essentially, anything went in terms of engines, provided you could get them to run through a race on a limited amount of fuel. This allowed production engines like the Aston and Mercedes V8s and Jaguar V12s to compete head to head with Mazda's rotary engines and Ford's Cosworth V8s. Some criticised the formula, saying that cars had to hold back early on or back off late in the race, but it produced a great variety of solutions, attracted many manufacturers and provided some great racing.

Every generation of race fan will have their own idea of the 'golden era' of racing, but for me, the 1980s are going to take a lot of beating. We had the sight and sound of Jaguar racing against Mercedes against Porsche and the massed ranks of the Japanese manufacturers (notably Mazda, Nissan and Toyota), with supporting roles played by Aston Martin, Spice, Ecurie Ecosse and many others.

Group C started, as so many good sportscar racing ideas do, at Le Mans. In 1978 Renault had won with a Group 6 (open 2 seater) sportscars, but to aid aerodynamics they'd fitted a bubble top, with just a small slit in front (for visibility) and a hole in the top (to ensure the car remained 'open' and complied with the rules).

This was possibly the catalyst for the GT prototype class which started at Le Mans. Bearing similarities to the great sportscars of the late 60s and early 70s (like the Ferrari 512s and Porsche 917s), these cars were basically closed group 6 cars.

Local Le Mans racer, Jean Rondeau was one of the first to embrace the rules building his cars especially for Le Mans and achieving a remarkable victory in 1980 as a local, owner-driver. The WM-Peugeots were also early exponents of the class, but whilst always fast (the fastest ever speed on the Mulsanne is held by a WM), they rarely lasted more than a handful of laps.

The very early days of Group C on an international level saw some oddities. The Lola T600, probably the first stab at a production Group C car, had to run with a hole in its roof at some events, which didn't recognise the Group C rules before the FIA ratified them.

Lola's T600 at Brands Hatch

The Kremer brothers, meanwhile, built a Porsche 917 and raced it in a handful of sportscar races including Le Mans and Brands Hatch in 1981.

Kremer's Porsche 917

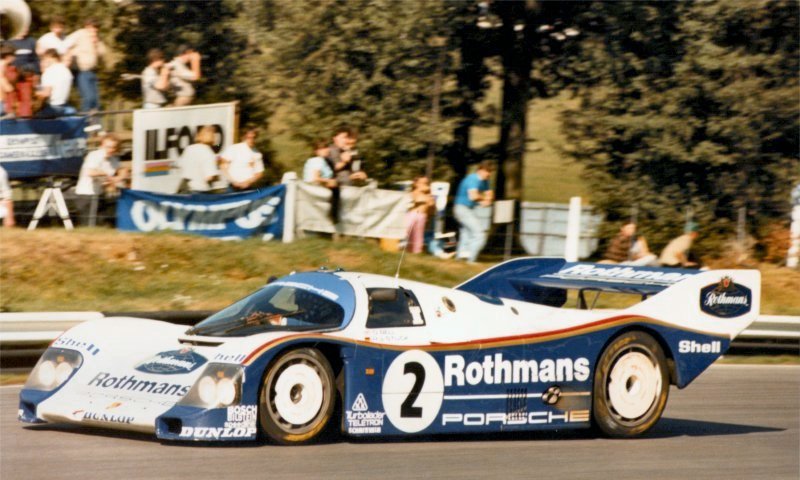

1982 saw the first Porsche 956s arriving on the racing scene. These were derived from Porsche's 936 group 6 car, but featured an enclosed cockpit. To many the 956 is the archetypal racing Sportscar shape.

Work's Porsche 956

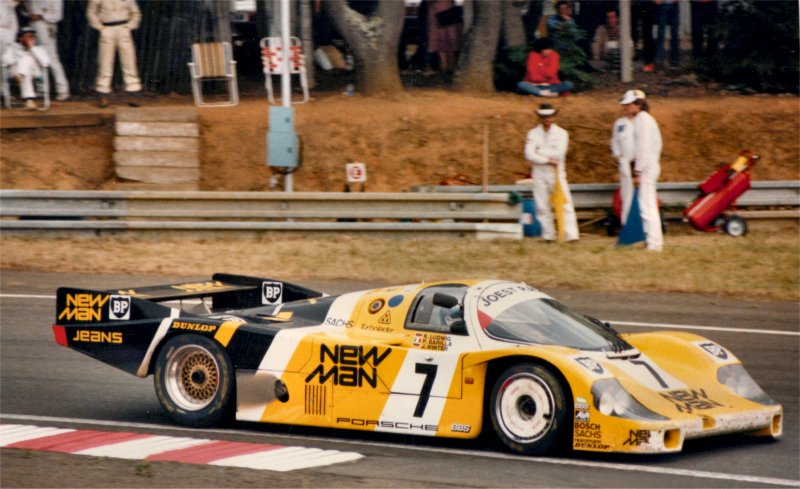

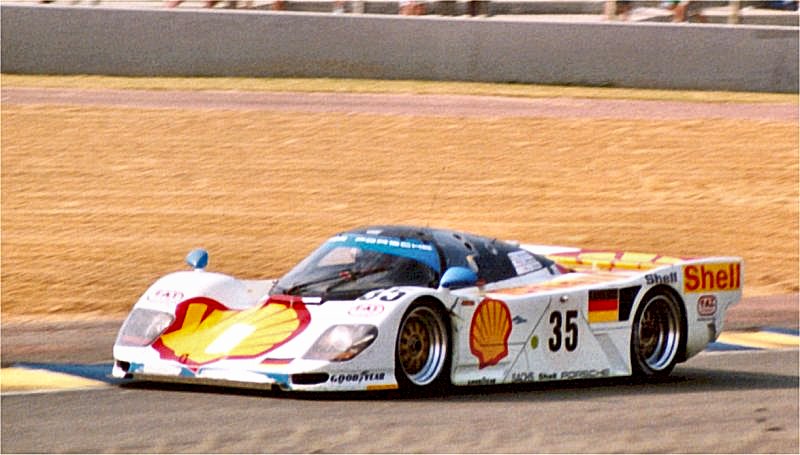

The 956 and the later 962 (differing mainly in moving the drivers feet behind the front wheels when the FIA rules feel in step with the IMSA rules the 962 was originally built for) became the mainstay for Group C, the way the 935 had for Group 5.

Whilst the factory raced a works team for much of the time, privateers also had a great deal of success with the car. Notable amongst these were :

- The Joest team (twice winners at Le Mans)

- The Brun team

- The Richard Lloyd Racing team (probably the most innovative Porsche team - building a carbonfibre chassised 962 and fitting rear wheel spats a la Jaguar).

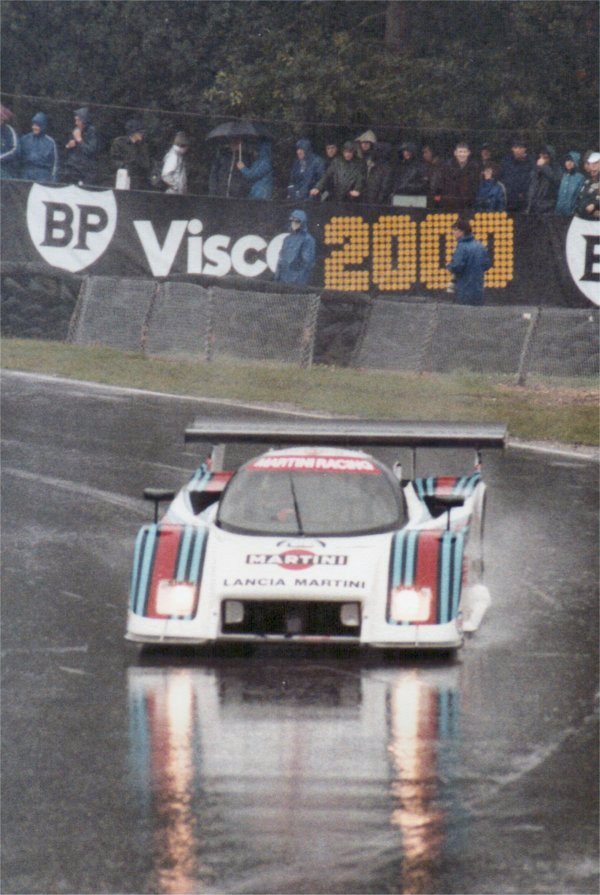

Lancia had been involved in sportscar racing for some while, winning the World Championship for Makes in the late 70s with a Montecarlo Group 5 car. At first, they used a lightweight Group 6 (open top) car fitted with the Montecarlo's 1.4 turbo engine, but this was not eligible for points in the WEC, so they quickly moved over to the beautiful LC2 (I'll be honest, this is my favourite Group C car on looks).

LC2 slither around a soaking Druids, Brands Hatch 1982

The barchetta ran, with a roof fitted, as the LC1 in a few races with a private team, but was hopelessly outclassed.

The LC2 was powerful and handled well. Lancia recruited F1 drivers, like Patrese and De Cesaris to drive them and it was more common than not to find an LC2 on pole for a race. Unfortunately, they lacked 100% reliability. Total failure was not common, but niggling faults often delayed the cars and, although, they did win 1000km races, Le Mans victory eluded them and the Porsches were always there to pick up the pieces.

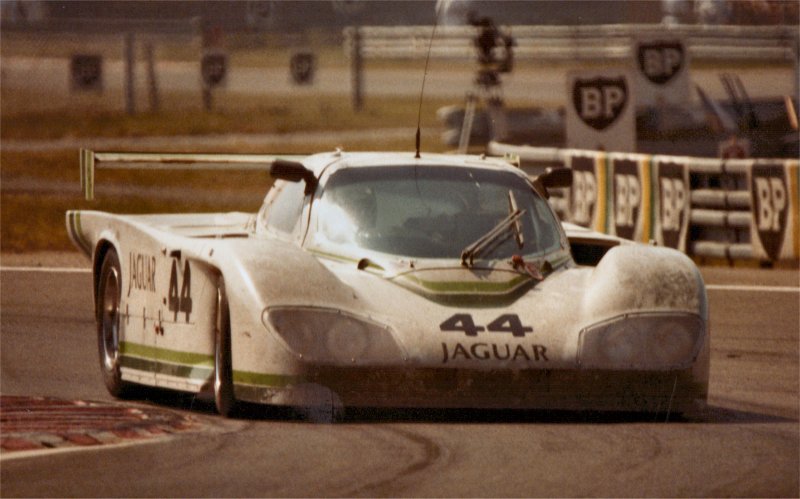

With Lancia failing to break the Porsche stranglehold, Group C looked in danger of becoming just another Porsche one make series, as Group 5 had been. However, after great success with the XJS in Touring Car racing and promising results in IMSA, the Jaguar management authorised the Bob Tullius run Group 44 Jaguars to run in the Le Mans 24 hours in 1984.

Above : One of the IMSA spec Group 44 Jaguar XJR5s at Le Mans, 1984

They ran well, scoring respectable finishes in 1984 and 1985, whilst never challenging for the lead, but Tom Walkinshaw, commissioned by Jaguar, concluded that to take on the Stuttgart cars he would need something more advanced than the aluminium semi-spaceframe cars, which were quite suitable for IMSA at that time.

The carbonfibre, monocoque, TWR Jaguars were common knowledge for much of 1985, but didn't actually appear until the tragic Mosport Park race in Canada (in which Manfred Winkelhock was killed). The British Racing Green Jaguar XJR6s ran well and scored a 3rd place finish for Schlesser, Brundle and New Zealander, Mike Thackwell.

Above : TWR Jaguar XJR6 at Brands Hatch, 1985

They also ran at Spa, where Brundle & Thackwell scored a 5th overall (after Stefan Bellof's tragic death) and Brands Hatch, where the cars proved fragile for Alan Jones, Jan Lammers, Martin Brundle and Mike Thackwell. However, the latter pairing did manage to record a sixth place on the Jags' first home appearance. Later in 1985, they scored an impressive 2nd in Shah Alam, Malaysia to round out the season, after withdrawing (along with all the other non-Japanese works teams) from the monsoon hit Fuji race.

In 1986, the improved cars were seen with Silk Cut livery for the first time. Immediately, they proved to be a threat to the formerly dominant Porsches and it didn't take long for Eddie Cheever and Derek Warwick to score the XJR6's first 1000km victory at Silverstone.

Above : TWR Jaguar XJR6 takes first victory at Silverstone, 1986

Other victories didn't come in 1986, but after a slightly disappointing Le Mans, where all three cars retired after showing well, a nail biting finish at Spa, saw Warwick fail to win by only a second or two as a faulty fuel pump failed to pick up the last drops of fuel. Boutsen's Brun Porsche 962C won.

Although, victory was elusive, the Jaguar's were always a threat and Warwick and Cheever were still in with a chance of snatching the team and driver's championships, going into the last round. However, they only finished in 3rd place. However, for a first full season, things had gone very well.

1986 also saw the arrival of the beautiful Kouros backed Sauber Mercedes. Driven by Mike Thackwell and always sounding as if they were about to expire with failed big ends, the turbo engined V8 car, derived from the Sauber C6 which had performed well with a gutless 3.5 litre BMW straight 6 engine (notably in Hans Stuck's hands at a wet Brands Hatch in 1983), were immediately on the pace of the Porsches and the Jaguars in practice, but not in race trim. At the time the cars were supposed to be privateer entries, but, with hindsight, it's apparent that Mercedes were behind the project from day 1, proving how strong Group C was becoming in attracting the big manufacturers. The car had first appeared, briefly, at Le Mans the previous year when John Nielsen had an airborne moment on the Mulsanne Straight (when it still was A straight) at over 200mph!

Above : Sauber-Mercedes C8 first run at Silverstone in 1986

Aside from the car's beautiful construction and finish (easily up with the Jaguars and Porsches), the car's most notable feature was the sound of the engine. Mercedes V8 turbos always sounded about to expire to me, but were monotonously reliable. If you've heard a Marcos LM600, that's the closest I've heard to the Mercedes, so maybe a NASCAR would be a similar sound, as the LM600's Chevrolet comes from that series.

In pouring rain, at the Nurburgring, Mike Thackwell's Goodyear tyres countered the Sauber's usual lack of downforce and he and Henri Pescarolo took victory, after Warwick's Jaguar retired with a broken oil line.

For a Jaguar Group C fan, like myself, 1987 and 1988 are probably the highlight years of Group C. 1987 saw Jaguars win 8 from the 10 races in the series. For Le Mans they went to great lengths to devise a special version of the car, with tilted engine/gearbox (to reduce strain on the driveshafts), open rear wheels (supposedly to aid pit stops, but probably also in attempt to cool the rear tyres) and low downforce wings. The battle between the formerly dominant Porsches and the Jaguars raged on until dawn, but the Jaguar's finally fell by the wayside and Porsche took victory once more.

1987 Le Mans Jaguar

The other flaw in Jaguar's record in 1987 came at the wierd Norisring circuit (around Hitler's old parade ground in Nurnburg and used to this day in the German STW (Touring Car) series). There, Jonathon Palmer took victory in Richard Lloyd's much modified Porsche 962C. This, carbonfibre chassised (by John Thompson) Porsche was less Porsche than Lloyd, but was the only Stuttgart car able to challenge the works cars in the later 80s.

The Kouros backed Sauber Mercedes and, for a while, Works Porsches, kept Jaguar honest, but the Saubers only ran in European rounds of the series and the works Porsches withdrew mid-season as the, soon to be stillborn, Indycar project started to consume Stuttgart resources.

In 1988, Mercedes stepped out of the Sauber shadow and, clad in AEG (part of Daimler Benz) sponsorship they took Jaguar on head to head. The first race fell to them, but the series and, at last, Le Mans was to go the way of Jaguar.

Le Mans saw the works' factory Porsches back, but the Jaguars were ready this time and, despite a titanic battle, they took the victory to great acclaim. The journey back to the ferry that year witnessed the slightly surreal sight of French people waving Union Jacks at British cars as they passed. It was 1944 all over again! This followed on from the TWR US team's victory at the Daytona 24 hours and the 12 Hours of Sebring, meaning a clean sweep of the true endurance races that year.

Throughout the year, however, Mercedes grew stronger and stronger (despite a Le Mans withdrawl prompted by massive tyre failure on Klaus Niedzwiez's car on the Mulsanne) and it was clearly they to whom Jaguar needed to look for competition in 1989.

By now, though, the Japanese manufacturers were beginning to take an interest. The lure of beating Porsche, Jaguar and Mercedes attracted them as a way of proclaiming the quality of their cars (although Nissan and Toyota's involvement did little to attract the likes of Jaguar and Mercedes).

Mazda had been running their rotary engined cars at Le Mans since the 1970s, but 1989 saw the first concerted efforts to take the big European makes on in Group C. Mazda's efforts were always low key (except at Le Mans), with their neat, but underpowered and underdeveloped cars. Nissan, by contrast, dove in in a big way, with their handsome Lola designed vehicle.

Nissan at Le Mans, 1990

Driven by now Indycar star, Mark Blundell, and former Mercedes man, Kenny Acheson, the Nissan showed well throughout the 1989 and 1990 season, with a well designed chassis and powerful turbo V8 engine.However, Nissan never quite broke into the triumverate of Porsche, Mercedes and Jaguar to take a victory, despite looking good for it on occasions.

Toyota, on the other hand, always seemed a bit half hearted about Group C, until, ironically, it was too late as the 3.5 litre rules took their toll. The main thrust for the Japanese, however, was always Le Mans and it was to long time contenders, Mazda, that the glory of being Japan's first winners fell.

Toyota's Group C car at Le Mans, 1988

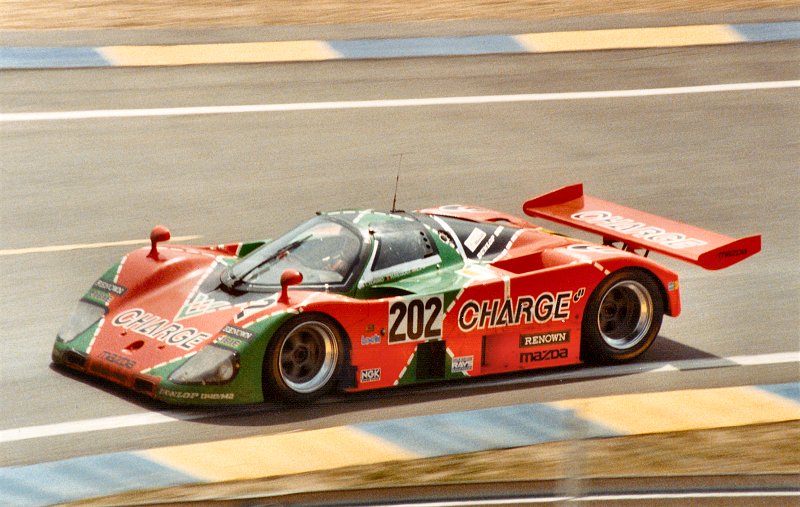

In 1991, Mazda gave the responsibility of running their entry to the French team, Oreca (now best known for running the Works Dodge Vipers in the FIA GT2 category). With F1 and F3000 drivers, Johnny Herbert, Volker Wiedler and Bertrand Gachot they took a well judged win ahead of 3 Jaguar XJR12s. To date, they remain the only Japanese team to win the 24 Hour classic.

From the earliest days of Group C, one of its strengths was the C Junior, later C2, class. This enabled privateers to enter, on a fairly small budget, and swell the fields to sensible numbers. Often C1 drivers would complain of slow and erratic C2 drivers, but it was a two way street and C1 drivers often pushed C2 cars off the road if they felt that they needed the bit of road the C2 was on.

C2 was killed off in 1992, when the FIA decided that all the privateers would be much happier running cars with F1 engines. Needless to say, even top C2 teams like Spice could not hope to compete with Mercedes and Jaguar and they all quietly went off to other projects or into liquidation.

In 1989, Mercedes dominated the WSC and the Le Mans 24 Hours. Arguably the highlight of the year was Le Mans where the team dominated (much, I'll admit, to my suprise) when conventional wisdom said they needed at least another year to do it. The team included Junior team member, Michael Schumacher, who exhibited some of the talent which was to make him, arguably, the world's greatest current driver, by lapping at speeds which had the Mercedes team management furious, but still being able to eke out extra laps per stint.

Jaguar, in contrast, lost their way somewhat as the V12 lost out in the escalating power battle with Mercedes turbo V8. To counter this, Jaguar produced the V6 turbo powered XJR11. This was definitely faster than the outgoing V12 XJR9, but it was fragile and not as quick as the C11 Mercedes.

In fact, in 1989, arguably the most promising British Group C car was Aston Martin's AMR1. At Brands Hatch, the XJR11's maiden event, the AMR1 took 4th place, ahead of the surviving Jaguar and it picked up a number of other good placings throughout the year.

Aston Martin AMR1 at Le Mans, 1989

As 1989 drew to an end, the Proteus team had built a 1990 spec AMR1, which was considerably lighter than the original car. However, Ford purchased Aston Martin (as well as Jaguar) and saw no need to have two of its marques fighting each other. The Aston project was folded up. This is probably a shame, as Jaguar had gleaned much kudos from their Group C programme and the same could have been done for Aston Martin, had Ford chosen to withdraw Jaguar from the series, instead.

1990 saw the FIA reduce race lengths to 480Kms (in an attempt to lure in TV coverage) and scrap the fuel limitation rules which had kept the balance between the teams for so long. Mercedes repeated their dominance, except at Silverstone, where the unloved XJR11 scored a notable 1-2.

Le Mans was not in the WSC that year, so Mercedes chose to sit it out and Jaguar returned with their V12 cars (now labelled XJR12s) and won convincingly against a returning Porsche works team. It's probably fair to say that Porsche blunted their chances by not competing in the WSC, but it was good to see them back.

In the other events, I recall an impressive showing by the 3.5 litre Spices at Donnington and consulting Martin Krejcimar's excellent results pages shows me that they indeed took 3rd overall in the hands of, current Marcos driver, Cor Euser and BTCC ace , Tim Harvey (in those days the route UP from Touring Cars was to sportscars).

The other in form team was Nissan, who scored numerous Seconds and Thirds throughout the season, taking over the place of chief challenger to Mercedes by the last couple of rounds when Jaguar's effort showed all the signs of having resources diverted from it to the design of the 1991 car.

Peugeot arrived on the Group C scene for the final couple of races in 1990. Their 3.5 litre car pointed the way to the future and mighty expensive it looked. The car, which looked two generations ahead of the current cars, sported a tiny cockpit, which drivers could bearly climb in and out of via removal plexiglass roof panels masquerading as doors and an all new V10 engine. It proved fragile in the races it took part in, but was clearly fast.

Indeed, 1991 dawned with a Peugeot victory at Suzuka, but the real revelation was the Jaguar XJR-14. The all purple car featured a full F1 Cosworth V8 and a body not much bigger, but more aerodynamic, than an F1 car. This car probably rates as one of the all time great sportscars as it appeared in 1992 as a Mazda and again, in 1996, with a Porsche engine as their WSC chassis. This went on to win Le Mans in both 1996 and 1997.

1991 Jaguar XJR-14 was almost a two seater F1 car

Warwick's pole time at Silverstone was fast enough to have put him on the 4th row for the Grand Prix.

After teething troubles in the first race, it dominated the next few to the extent that Peugeot went away a completely redesigned the 905 to reappear as the 905B, outwardly similar, but radically different. Mercedes, by contrast, plodded on with the old fashioned C291, having completely misjudged the level of competition from Peugeot and Jaguar.

Le Mans, as already mentioned, went the way of Mazda's rotary engined car, much to everyone's delight, ahead of a trio of V12 Jaguars.

Mazda win at Le Mans, 1991

By the end of 1991, the writing was on the wall. The shortened races (which didn't appeal to TV or 'sprint' race fans and annoyed endurance race fans) and cost of 3.5 litre cars (spiralling upwards due to F1 and aerospace technology) were driving spectators, sponsors and competitors away in droves. Jaguar and Mercedes (who clinched a late season win with their C291 as poor consolation for a terrible season for them) both announced their withdrawl from Group C, not keen to spend lots of money to loose out to 'down market' marques such as Toyota and Peugeot.

Peugeot 3.5 litre 905B in the rain at Le Mans (not my photo)

A series did take place in 1992, but with just Peugeot and Toyota taking part. Very few privateers had either the funds or the inclination to take part and, after a number of races just faded away, the World Sportscar Championship ceased to be. Peugeot, for the record, won all but the first, Monza, race, which was taken by the Toyota TS010 of Geoff Lees. Everyone else was, frankly, an also ran.

Typically, in 1992, fields were under a dozen cars of which only 4 were truly competitive. The Euro Racing Lola's often scored good placings, but well behind the works cars and the Mazda MXR-01 (1992's XJR14) was rarely on the pace, due mainly to lack of funding, although it did run strongly at Le Mans.

So the crazy FIA decision to revoke fuel economy rules, shorten races for TV coverage which didn't appeal to 'sprint fans' and annoyed endurance supporters and the introduction of F1 based 3.5 litre rules finally killed off the great Sportscars.

Some say that F1 'wheeler-dealer' Bernie Ecclestone was keen to attract Mercedes and Peugeot into F1 and the demise of Group C did achieve that. It's also probably true that he was keen to see Group C's small, but growing, impact on F1 publicity curtailed.

Last run for the C cars - Toyota TS010 at Le Mans in 1994.

The Group C Toyotas and Peugeots did battle at Le Mans again in 1993, with Peugeot again victorious.

The final race featuring Group C cars was at Le Mans in 1994, when Toyota came back, for last hurrah, but they were narrowly beaten by the 'GT' Dauer Porsche 962C (a developed Group C car running on narrow tyres).

Dauer's Porsche 962 'GT' car - Le Mans 1994 winner.

Perhaps, looking back over the Group C era, this was poetic justice...

If you'd like to know more about Group C (And the IMSA racers of the same period), there is an excellent two book boxed set called "The Golden Era".

Co-Author, John Starkey, has more details on his website, where you can buy the book from.

Back To The Sportscar Racing Page